How to Conduct and Document an Initial Assessment for ABA Services

What Is an Initial Assessment in ABA?

An initial assessment is the foundation of every effective ABA program. It’s where we determine medical necessity, identify why challenging behavior occurs, and pinpoint which skill deficits are holding a learner back. More importantly, it’s our first opportunity to build trust—with the learner and their caregivers. A strong start here sets the tone for the entire treatment experience.

At its core, an initial assessment has two essential components:

1. Behavioral Assessment

This piece identifies why challenging behavior occurs. You analyze patterns, triggers, maintaining consequences, and environmental variables so you can design a function-based plan that actually works.

2. Skills Assessment

Challenging behavior makes sense when we understand the missing skills underneath it. The skills assessment pinpoints communication, self-regulation, social, play, and adaptive skill deficits that directly contribute to problem behavior.

Why This Matters

The initial assessment is more than paperwork:

It frames expectations and establishes the caregiver’s role in treatment.

It sets the standard for ethical, medically necessary care.

And it guides goal selection so treatment is meaningful—not just a checklist of skills.

If this part is rushed or unclear, everything built on top of it becomes shaky. But when it’s done well, the treatment plan becomes a roadmap for real, measurable progress.

How to Conduct and Document an Initial Assessment for ABA Services

What Is an Initial Assessment in ABA?

Before the Assessment: Setting the Foundation for Accuracy + Trust

1. Review All Available Documentation

2. Gather Materials for Both Behavioral + Skills Assessment

3. Choose Your Assessment Methods

4. Prepare the Environment (If You Control the Setting)

5. Develop Contingency Plans Before You Arrive

If the learner has more skills than expected:

If the learner participates less than expected:

If no challenging behavior occurs:

6. Visualize the Assessment Flow

Conducting the Behavioral Assessment (FBA): Your Foundation for an Effective Treatment Plan

What Is a Behavioral Assessment?

Choosing the Right Behavioral Assessment Method

1. Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

3. Practical Functional Assessment (PFA)

Defining Target Behaviors: The Step You Cannot Rush

Indirect Assessments: Gathering Context Before You Observe

Direct Assessment: Where You See the Story Unfold

Conducting a Behavioral Assessment (Simplified, Practical Overview)

Step 1: Choose the Right Behavioral Assessment Method

Step 2: Define the Target Behaviors

Step 3: Conduct Indirect Assessments

Step 4: Conduct Direct Assessments

Step 6: Document Your Findings

Conducting the Initial Skills Assessment

Step 2: Build Rapport Before Testing

Step 3: Allow Open Exploration

Step 4: Probe Skills Systematically (But Flexibly)

Step 5: Collect Meaningful, Interpretable Data

Step 6: Debrief With Caregivers

Documenting the Assessment (Without the Overwhelm)

What to Include in the Assessment Documentation

1. Basic Assessment Information

2. Summary of Records Reviewed

3. Behavioral Assessment Summary

Tone and Documentation Priorities

Prioritizing Target Skills Based on Assessment Results

Start With Skills Directly Related to Challenging Behavior

Choose Skills That Promote Independence

Follow the “1 Goal per Hour” Rule

Writing the Treatment Plan: Turning Assessment Data Into Action

1. Start With the “Why”: Medical Necessity

2. Summarize the Assessment Clearly and Concisely

3. Present Target Behaviors and Hypothesized Functions

4. Include a Clear, Practical Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)

5. Translate Assessment Findings Into Skill Acquisition Goals

6. Outline Parent or Caregiver Participation Expectations

7. Describe Your Plan for Monitoring and Adjusting Treatment

8. End With Discharge Criteria and Projected Duration of Treatment

Conclusion: Laying the Foundation for Effective, Ethical, and Impactful ABA Services

Before the Assessment: Setting the Foundation for Accuracy + Trust

A successful initial assessment doesn’t start when you walk into the home, clinic, or school. It starts days earlier, as you prepare your materials, review records, and anticipate the needs of both the learner and their caregivers. This stage is where you build the foundation for accurate data, smoother rapport-building, and a strong start to the BCBA–family partnership.

Too many new BCBAs® rush into the assessment without the right preparation. The result? Missed information, preventable barriers, and the need for repeated sessions. You can avoid all of this with a systematic, thoughtful pre-assessment workflow.

Want to earn CEUs while learning everything you need to know about Conducting and Documenting an Initial Behavioral and Skills Assessment? Join the Master ABA Dojo today and get access to our CEU course!

1. Review All Available Documentation

Record review is your first window into the learner’s world. You're not just gathering facts — you’re shaping hypotheses that guide what you probe, what you prioritize, and what safety considerations you prepare for.

Review documents such as:

Intake forms

Diagnostic evaluations

IEPs

Previous ABA or related service reports

Medical information

Parent questionnaires

Therapy notes or disciplinary records (when available)

As you review these records, pay special attention to:

Patterns of behavior

Reported triggers

Skill strengths

Suspected deficits

Contexts where behavior is most and least likely

Safety concerns

2. Gather Materials for Both Behavioral + Skills Assessment

Your preparation should cover every data-collection need — and multiple contingency plans. A well-prepared BCBA wastes zero time searching for materials in the moment.

Bring:

Behavioral questionnaires (FAST, MAS, QABF)

Parent interview questions

Clipboards, notebooks, pens

Stimuli for probing communication, play, and matching

High-interest toys for pairing

Visuals, picture cards, mini objects

Assessment manuals (VB-MAPP, AFLS, etc.)

Preferred items for potential reinforcers

Pro tip: Color code your notes — behavioral assessment observations vs. skills assessment data — so data organization is effortless later.

3. Choose Your Assessment Methods

This is where many BCBAs struggle. The choice affects everything downstream — the precision of your functional hypotheses, the usefulness of your goals, and ultimately the medical-necessity justification.

You will choose:

Behavioral Assessment Method

FBA

FA

PFA

The vast majority of initial assessments rely on a descriptive FBA, but prepare backup plans in case the behavior does not occur.

Skills Assessment Tool

VB-MAPP

AFLS

ABLLS-R

PEAK

ESDM

EFL

Think about:

Funding requirements

Learner’s age and developmental level

Scope of needed skills

Your own training

Available materials

Your goal isn’t to choose the perfect tool — it’s to choose the one that best aligns with the learner’s needs at this moment.

4. Prepare the Environment (If You Control the Setting)

A poor environment sabotages your assessment. A well-prepared one accelerates rapport, engagement, and the accuracy of the results.

Set up the space by:

Removing unnecessary distractions

Placing interesting items in view but out of reach

Sprinkling accessible items around to assess manding, exploration, and play

Ensuring all safety hazards are removed or secured

This also sets the stage for naturalistic opportunities to observe:

Manding

Social approach behaviors

Tolerance for denied access

Play skills

Transitions

5. Develop Contingency Plans Before You Arrive

You never want to be caught unprepared. Plan for:

If the learner has more skills than expected:

Have additional assessment materials ready

Be prepared to jump levels in the skills assessment

If the learner participates less than expected:

Pair longer

Use parent-assisted probing

Shift into caregiver-led demonstrations

If no challenging behavior occurs:

Request naturalistic video recordings

Train caregivers to collect ABC data

Schedule a follow-up observation

If unsafe behavior occurs:

Ask caregivers to demonstrate their typical response

Call for clinic support (center-based)

Pause the assessment and reschedule if needed

Prepared BCBAs® create safer, smoother, more accurate assessments — period.

6. Visualize the Assessment Flow

Before assessment day, mentally rehearse:

How you’ll greet the family

How you’ll enter the space

How you’ll pair

How you’ll move through probing

What you’ll do if the learner refuses

What you’ll do if behavior escalates

What you'll do if the learner surprises you with higher skills

This is not fluff — it’s procedure. Visualization strengthens clinical decision-making and reduces your cognitive load on assessment day.

Conducting the Behavioral Assessment (FBA): Your Foundation for an Effective Treatment Plan

A high-quality initial assessment always includes a clear, efficient, and defensible approach to understanding why challenging behavior occurs. This is where the behavioral assessment shines. As a BCBA®, this is the anchor of your clinical decision-making—and arguably the most essential piece of your entire treatment plan.

Data for an FBA comes from at least 3 sources. This ensures an adequate sample of the behavior to build confidence in your diagnosis of the function of the behavior. Most commonly, your data will come from a review of existing records (i.e. incident reports from school), indirect assessments, and finally your direct observation. The data you collect during the observation (the direct assessment) connects with the indirect assessment data to help you form a hypothesis.

What Is a Behavioral Assessment?

A behavioral assessment aims to identify the function of challenging behavior and the environmental variables that maintain it. Without this information, your intervention plan is guesswork—and ineffective intervention risks reinforcing the very behaviors we want to reduce.

A thorough behavioral assessment typically includes:

Choosing the assessment method

Defining target behaviors

Conducting indirect assessments

Conducting direct assessments

Collecting and analyzing data

Documenting results

Choosing the Right Behavioral Assessment Method

Most ABA practitioners rely on one of three primary methods:

1. Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

The most common, accessible, and widely accepted method.

Pros: Easy to implement, gathers information from multiple sources, avoids evoking dangerous behavior.

Cons: Less precise than FA; results in a hypothesis about function.

Best for: Insurance-funded ABA, home programs, schools, early learners, and situations where safety is a concern.

2. Functional Analysis (FA)

The “gold standard,” but not always feasible.

Pros: High accuracy; identifies function with experimental control.

Cons: Requires training, time, controlled conditions; risk of evoking behavior.

Best for: Controlled clinical settings, teams trained in FA implementation, and cases where previous FBAs produced unclear results.

3. Practical Functional Assessment (PFA)

Developed by Dr. Greg Hanley, this approach synthesizes multiple maintaining variables and prioritizes safety.

Pros: Accounts for complex behavior patterns, reduces risk, integrates caregiver interview.

Cons: Often requires additional training; not always taught in graduate programs.

Best for: Behaviors with multiple potential functions, learners with long histories of challenging behavior, or environments where precision and safety must be balanced.

Defining Target Behaviors: The Step You Cannot Rush

Operational definitions are the backbone of accurate data collection. A strong definition includes:

Clear, observable description

At least 2 examples

At least 2 non-examples

Example:

Flopping: The learner’s body goes limp, resulting in kneeling or lying flat on the floor.

Examples:

Falling to knees while walking.

Dropping to the floor after an adult gives a directive.

Non-examples:

Lying down as part of a game.

Kneeling appropriately during circle time.

Tip: Limit your target behaviors to three or fewer. Too many targets dilute your ability to collect meaningful data.

Indirect Assessments: Gathering Context Before You Observe

Indirect assessments should narrow your focus, not replace observation. These tools include:

Caregiver interviews

Teacher or stakeholder interviews

Questionnaires (FAST, MAS, QABF)

Rating scales (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales)

Indirect assessments help you identify:

Possible setting events

Predictable triggers

Patterns across settings

Caregiver perceptions

A history of successful or failed interventions

This step also builds rapport and helps families feel heard—an essential part of compassionate ABA. Check out our post: ABC Data: The Key to Understanding Behavior.

Direct Assessment: Where You See the Story Unfold

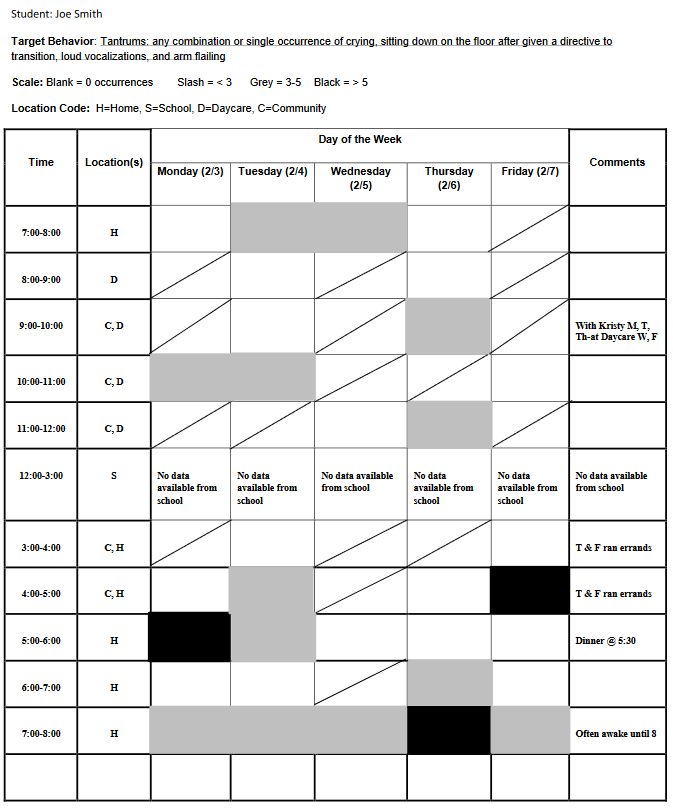

Direct observation is the most powerful form of behavioral assessment. Depending on the method, you may collect:

ABC data

Frequency, rate, or duration

Scatterplot data

Latency (for PFA)

When behavior does not occur during your scheduled observation, get creative:

Ask caregivers to record a safe clip of behavior

Conduct observation at a different time of day

Observe routines where the behavior typically occurs

Schedule multiple short observations

Important: Direct assessment should confirm or challenge your indirect assessment—not simply match it.

If you're going to ask someone else to collect ABC data (i.e. parents, teachers, etc.), consider using an ABC data sheet with checkboxes like the one below. This allows for a more consistent reporting of antecedents and consequences that are easier to analyze.

Conducting a Behavioral Assessment

A behavioral assessment is the backbone of every ABA treatment plan. Its purpose is simple but powerful: identify why challenging behavior occurs so you can design interventions that actually work.

Step 1: Choose the Right Behavioral Assessment Method

Before you collect any data, you must determine how you’re going to assess the behavior.

Common options include:

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) – the most widely used approach in clinical ABA.

Functional Analysis (FA) – high precision but more intrusive and rarely feasible in insurance-funded settings.

Practical Functional Assessment (PFA) – a modern, trauma-assumed, synthesis-based approach.

Each method has strengths and limitations. For most initial assessments, the FBA is the appropriate and funder-aligned choice.

For more detailed information, read our post: Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP): The Complete Guide.

Step 2: Define the Target Behaviors

Clear operational definitions protect the integrity of your assessment. They must include:

A precise description

At least two examples

At least two non-examples

This ensures everyone on the treatment team is aligned and allows for accurate baseline data and analysis.

For more detailed information read our post: Operational Definitions: Clearly Define the Behavior.

Step 3: Conduct Indirect Assessments

Indirect assessments help you narrow your focus before beginning direct observation.

These may include:

Parent/caregiver interviews

Teacher interviews

Review of existing documentation (IEPs, notes, prior reports)

Questionnaires (FAST, MAS, QABF)

Done correctly, indirect assessments help identify:

Potential antecedents and consequences

Situations where behavior is more or less likely

Possible skill deficits

Safety considerations

Stakeholder perspectives and concerns

This information becomes the blueprint for your direct observations.

There are several commonly used questionnaires to help you diagnose behavioral function including:

They each serve essentially the same purpose so it's unnecessary to use more than one. These data should also be graphed on a bar graph since it does not depict changes in the behavior over time. The x-axis depicts the possible functions and the y-axis is the average score (or total score depending on the questionnaire) for each function.

Example graph of QABF questionnaire results

Step 4: Conduct Direct Assessments

Direct assessments allow you to observe behavior in real time and understand the controlling variables.

Common direct data collection methods include:

ABC data (open-ended or structured)

Frequency, rate, or duration data

Scatterplots (when behavior varies by time or routine)

Your goal is not to "catch" every behavior but to collect enough high-quality samples to form a reliable hypothesis.

For more information on collecting descriptive assessment data, read our post: ABC Data: The Key to Understanding Behavior.

Step 5: Analyze the Data

A strong behavioral assessment translates raw data into clear patterns. Your analysis should:

Identify the most consistent antecedents

Identify the most probable maintaining consequences

Consider setting events

Evaluate multiple data sources for convergence

Address potential sources of bias in analysis

Analysis is where you move from information to insight, forming your hypothesis of behavioral function. For more information about functions of behavior, read our post: Functions of Behavior in ABA: A Complete Guide.

You can summarize the data in a problem behavior pathway, a simple statement that includes the most common ABCs:

Include common setting events as you will use this information when completing the Competing Behavior Pathway in the next step. List the most common antecedent based on the data you collected. Include all the behaviors that occur in the context you're describing, even if they don't co-occur in every incident. Finally, describe the consequence that maintains the target behavior(s). See the example below where the learner engages in 3 different target behaviors within this one context.

Complete the Competing Behavior Pathway to Guide Intervention Selection

The Competing Behavior Pathway is a visual representation of the learner's target behavior with the current maintaining variables and a more desirable pathway that includes functionally equivalent replacement behaviors. The pathway (see the image below) includes space for both:

Replacement Behavior-an acceptable alternative to the target behavior (usually a communicative response) that allows the learner to access the maintaining consequence

Desired Behavior-the terminal response that will take the place of the target behavior (this often involves some sort of tolerance)

The top row of the pathway comes from the Problem Behavior Pathway. List the most common setting event, antecedent, behaviors (that occur in this context) and consequence.

Next, identify the replacement behavior. This might not be what you ultimately want the learner to do in this context, but it provides the learner with a better way to get what he/she wants without engaging in the target behavior. This behavior is an intermediate step to your end goal. This should always directly relate to the function of the target behavior.

Finally, the bottom row of the pathway includes accommodations or interventions you recommend to help the learner make the leap from the Replacement Behavior to the Desired Behavior. See the example below.

Get a free, fillable Competing Behavior Pathway.

Step 6: Document Your Findings

Your documentation should be:

Clear

Objective

Organized

Devoid of jargon (when parents or funders are the primary audience)

Your behavioral assessment write-up becomes the foundation for:

Medical necessity

Treatment authorization

Your BIP

Your skill acquisition plan

Conducting the Initial Skills Assessment

A high-quality assessment does more than identify what a learner can’t do. It reveals the skills they are ready to acquire, helps you understand how they learn best, and begins shaping a treatment plan grounded in dignity, compassion, and medical necessity. While every assessment looks a bit different, all effective evaluations share the same goals: accuracy, efficiency, and relevance to the learner’s real-life needs.

The skills assessment involves fewer steps than the FBA but it's critical to developing a comprehensive treatment plan. Learners engage in challenging behavior because they lack the skills to do better. As notable psychologist Dr. Ross Greene said, "kids do well if they can." It's the job of the skills assessment to figure out what skills the learner is missing.

Kids do well if they can.

Dr. Ross Greene

In the video below, Dr. Stuart Ablon discusses this concept in a compelling TEDX Talk. He helps create a frame for thinking of challenging behavior as related to the learner's skill deficits. Adopting this frame before conducting a skills assessment encourages you to look for the connection between the learner's behaviors and skill deficits.

Step 1: Plan and Prepare

Before you interact with the learner, invest time in preparation. Planning allows you to stay present during the assessment rather than scrambling for materials or information.

What to review beforehand:

Diagnostic reports

Previous assessments

IEP or school documentation

Notes from other providers (speech, OT, PT, psychiatry)

Intake forms and caregiver interview data

This pre-assessment review helps you predict potential barriers, identify high-priority skills, and avoid duplicating assessment content completed by other providers.

Materials to gather:

Your selected assessment protocol (e.g., VB-MAPP, ABLLS-R, AFLS)

Notepad + clipboard or tablet

Reinforcer options

Naturalistic play items

Visuals or AAC systems the learner already uses

Miscellaneous tools for probing skills (books, puzzles, manipulatives, etc.)

Preparing the environment—removing distractions, placing motivating items in view but out of reach, and clearly structuring the space—sets the stage for both naturalistic probing and structured testing.

Step 2: Build Rapport Before Testing

A cold start produces unreliable data. Take 10–15 minutes to connect with the learner:

Follow their lead in play

Offer simple social bids without pressure

Pair yourself with preferred activities

Observe communication, joint attention, and play skills naturally

This rapport period is data-rich—often more revealing than formal testing—and can help you identify natural entry points for skill probes.

Step 3: Allow Open Exploration

A short exploration period gives you opportunities to observe:

Manding

Spontaneous language

Play level

Tolerance for novelty

Transitions within the environment

Problem behavior patterns

Social approach behaviors

This is essentially a loosely structured free-operant preference assessment, which also helps you determine whether your selected reinforcers actually function as reinforcement during assessment.

Step 4: Probe Skills Systematically (But Flexibly)

This is where most BCBAs® try to rush—yet slowing down makes your results far more accurate.

Guidelines for effective probing:

Start with skills the learner is likely to succeed with to build momentum.

Move fluidly between structured and naturalistic opportunities.

Present higher-level tasks first if appropriate (e.g., LRFFC in a field of six), then work backward if needed.

Avoid teaching during the assessment. Simply re-probe later in a different context.

Note barriers to performance—not just incorrect responses.

Good probing answers the question:

What is this learner capable of under optimal conditions—not just what they demonstrated in one moment?

You have a lot of options to choose from when selecting a skills assessment. Use the decision tree below to help you choose the one that might be the most appropriate for your learner.

One of the most common assessments is the VB-MAPP by Dr. Mark Sundberg. This is due to the acceptance of the assessment by funders, the easy of use, and the most common needs of the children entering into ABA services.

The video below by Good Behavior Beginnings provides a demonstration of the VB-MAPP assessment conducted with a 2-year-old.

Step 5: Collect Meaningful, Interpretable Data

Your raw notes are messy by design—that’s okay. What matters is that you gather enough information to:

Identify prerequisite deficits

Establish clear baselines

Reveal patterns that connect skill deficits to challenging behavior

Justify treatment goals with objective data

Data to capture:

Score sheets from the formal assessment

Anecdotal notes on communication, play, and social behavior

Reinforcer preferences

Signs of avoidance, frustration, or task refusal

Skills that differ from caregiver report

These details will later support the medical necessity justification in your treatment plan.

Use indirect assessments to round out your understanding of the learner's skills. During your direct assessment, you will only get a quick snapshot of what the learner is willing to do for a total stranger. Indirect assessments give you a more robust picture of their skills.

An indirect assessment is any assessment that doesn't involve you directly measuring the behavior or skill. Indirect assessments provide an alternative when the barriers discussed earlier prevent you from obtaining accurate assessment data. These assessments typically include rating scales completed by the parent or someone who knows the learner well such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-3.

In the video below, Joe Dixon, BCBA® discusses the use of the Vineland-3. The video begins with an introduction to assessments which might be of interest, but he starts talking about the Vineland-3 at minute 22.

Step 6: Debrief With Caregivers

Your closing conversation shapes expectations, clarity, and trust. In this brief meeting:

Clarify any unusual or unexpected assessment findings

Ask caregivers whether skills observed are typical

Review next steps and timelines for documentation and authorization

Share anticipated priorities (communication, self-management, independence skills, etc.)

Reaffirm the caregivers’ role in treatment

This is also your chance to set the foundation for effective parent training, a hallmark of successful ABA programs.

Documenting the Assessment

Documentation is where many BCBAs® start to feel the weight of the initial assessment—but it doesn’t have to be that way. When you streamline your structure and focus on what funders actually care about, the process becomes more purposeful, more efficient, and far less stressful.

Your documentation should do three things:

Demonstrate medical necessity

Show clear clinical reasoning

Create a roadmap for the treatment plan

Here’s a clean, simplified structure that keeps your report powerful without becoming bloated.

What to Include in the Assessment Documentation

1. Basic Assessment Information

This section should allow someone to understand who conducted the assessment, when, and why. Include:

Assessment date(s)

Evaluator name and credentials

Reason for referral

Anticipated start date of services

Keep this short. This is not a biography—this is orientation.

2. Summary of Records Reviewed

Briefly list the documents reviewed (e.g., diagnostic report, IEP, prior assessments).

The purpose is to show thoroughness and confirm that your plan is grounded in existing information.

3. Behavioral Assessment Summary

This should synthesize—not replicate—the full FBA content from earlier.

Include:

Target behaviors with operational definitions

Summary of indirect assessment findings

Summary of direct observation

Hypothesized functions of behavior

Avoid including raw data tables unless the funder requires them. Keep the narrative tight and clinically rich.

For a deeper walkthrough of conducting and analyzing FBAs, see our post: Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP): The Complete Guide.

4. Skills Assessment Summary

Highlight only the information that:

Supports medical necessity

Informs replacement behaviors

Guides your skill acquisition programming

Include:

Which assessment(s) were used

Key strengths

Key deficits relevant to treatment

Barriers to accurate responding (if applicable

– e.g., behavior, motivation, attention, rapport)

5. Clinical Interpretation

This is where you demonstrate your expertise.

Answer:

What skills does the learner lack that directly contribute to challenging behavior?

Which skill deficits most limit independence?

What does the learner need to participate meaningfully in daily routines?

This is your bridge between the assessment and the treatment plan.

6. Recommendations

This must be clear, measurable, and defensible. Include:

Location of services

Proposed hours (with rationale)

Parent training expectations

Behavior analytic interventions likely to be used

Any immediate safety considerations

This is one of the most important sections for insurance reviewers—be specific and confident.

Tone and Documentation Priorities

Funders want:

Clarity

Consistency

Clinical justification

Parents want:

Plain-language explanations

Confidence in your expertise

Transparency

You must balance both.

Avoid jargon unless your audience expects it. Always use person-first, dignifying language. And stay concise—excessive detail does not make the assessment look more professional; it makes it harder to interpret.

Prioritizing Target Skills Based on Assessment Results

Once you’ve gathered both behavioral and skill-based data, it’s time to determine what truly matters for this learner right now. This is where many new BCBAs® get overwhelmed—because everything can feel important. But effective programming demands strategic prioritization, not a kitchen-sink treatment plan.

Your goal is simple:

Target the skills that will meaningfully reduce challenging behavior and increase independence.

Everything else can wait.

Start With Skills Directly Related to Challenging Behavior

Challenging behavior almost always communicates a skill deficit. When you identify that deficit, you uncover the most powerful leverage point for treatment. Ask yourself:

What skill would immediately reduce the learner’s need to engage in this behavior?

What prerequisite must be in place for the replacement behavior to succeed?

Common high-leverage areas include:

Manding for wants/needs

Tolerance for delays or denied access

Basic self-management skills (waiting, transitioning, accepting “no”)

Reinforcer effectiveness (expanding the learner’s preferred items and activities)

These skills almost always move the needle quickly—and documentation clearly aligns with medical necessity.

Choose Skills That Promote Independence

Beyond behavior reduction, focus on skills that make everyday life easier, but you might need to phrase these as aligned with a core deficit of autism such as social skills:

Self-care (toileting, feeding, dressing)

Safety skills

Functional communication

Play and leisure (critical for decreasing restricted attention-seeking behavior)

Social skills required for group participation

These selections support long-term outcomes and create a more robust, future-proof learner repertoire.

Avoid “Teaching to the Test”

This is a trap many clinicians fall into. Remember:

Your goal is not to chase VB-MAPP boxes. Your goal is to change the learner’s life.

Use assessments as a guide—not a checklist.

Instead of simply targeting the next unmastered milestone, ask:

Will this skill matter outside this room?

Will it reduce barriers?

Will it open meaningful opportunities?

If the answer is no, it’s not a priority.

Follow the “1 Goal per Hour” Rule

A simple planning heuristic:

For every hour of recommended direct treatment, include roughly one skill acquisition program.

Example:

20 direct hours = ~20 programs across communication, play, social, functional living, and self-management.

This keeps programs manageable for RBTs, realistic for the learner, and appropriately justified for funders.

Writing the Treatment Plan: Turning Assessment Data Into Action

Your assessment only becomes meaningful when it’s translated into a clear, defensible, and actionable treatment plan. This is where you demonstrate clinical reasoning, justify medical necessity, and outline a roadmap that caregivers, technicians, and funders can follow with confidence. A strong ABA treatment plan tells a coherent story: what you observed, why it matters, and how behavior change will be achieved.

1. Start With the “Why”: Medical Necessity

Funders want clarity and precision. Your treatment plan must directly connect the learner’s deficits and interfering behaviors to clinically significant barriers. Strengthen this section by:

Describing how skill deficits contribute to challenging behavior

Identifying risks to health, safety, or long-term functioning

Highlighting how ABA will address barriers that other services cannot

Linking every goal to functional, not academic, outcomes

A clean, compelling medical necessity narrative helps secure authorization and protects the integrity of your case.

If you want deeper guidance on medical necessity, check our our: Understanding Medical Necessity Guide.

2. Summarize the Assessment Clearly and Concisely

This is not the place to dump raw data. Instead:

Highlight major findings from your FBA

Summarize relevant results from your skills assessment

Identify priority areas interfering with learning or independence

Note any barriers that affected assessment accuracy

This section should give the reader a fast, intuitive grasp of the learner’s needs and how you identified them.

3. Present Target Behaviors and Hypothesized Functions

You've already built the foundation in earlier sections. Now, simply:

Provide operational definitions (brief but specific)

List baseline data

Identify hypothesized function for each behavior

Connect behavior patterns to environmental variables

This creates a smooth bridge into your Behavior Intervention Plan.

4. Include a Clear, Practical Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)

Your BIP should reflect the principles outlined in the Competing Behavior Pathway:

Antecedent strategies that prevent escalation

Replacement behaviors directly tied to behavioral function

Skill acquisition targets that promote long-term independence

Consequence strategies aligned with reinforcement, not punishment

Crisis procedures, only if behavior presents safety risks

A BIP is strongest when it prioritizes compassionate, learner-centered supports over compliance-based approaches.

5. Translate Assessment Findings Into Skill Acquisition Goals

Skill acquisition goals should:

Address missing skills contributing to challenging behavior

Support independence and everyday functioning

Generalize naturally across settings

Be observable, measurable, and medically necessary

Align with the learner’s motivators and developmental stage

A helpful rule of thumb: one skill acquisition program per recommended hour of direct ABA. But quality trumps quantity—avoid “teaching to the test.”

6. Outline Parent or Caregiver Participation Expectations

This is a non-negotiable requirement from most funders. Clarify:

Frequency and format of parent training

Caregiver responsibilities during sessions

Key skills you will teach to promote generalization

Expectations for implementing strategies between sessions

Emphasize that caregiver involvement is essential—not optional—for meaningful and durable progress.

7. Describe Your Plan for Monitoring and Adjusting Treatment

Every effective ABA plan is dynamic. Document:

How often you will review data

How you will supervise RBT implementation

What criteria you use to modify programs

How treatment integrity will be maintained

This demonstrates ongoing clinical oversight—something insurers expect to see clearly.

8. End With Discharge Criteria and Projected Duration of Treatment

Funders want assurance that ABA is a time-limited, goal-oriented intervention. Include criteria such as:

Reduction of target behaviors to clinically acceptable levels

Mastery and generalization of targeted skills

Caregiver ability to independently implement strategies

Transitioning to less intensive services when appropriate

This communicates both accountability and long-term planning.

Conclusion: Laying the Foundation for Effective, Ethical, and Impactful ABA Services

A well-executed initial assessment isn’t just a procedural requirement—it’s the engine that drives meaningful, compassionate, and effective ABA intervention. When you break the process into clear, manageable steps, you gain the clarity needed to design treatment that is ethical, individualized, and rooted in genuine medical necessity. From identifying the function of behavior to selecting skill acquisition targets that truly matter, your assessment sets the trajectory for every success that follows.

Strong assessments empower learners, support families, and elevate the quality of your clinical decisions. They also protect your credibility as a behavior analyst—especially when your documentation is anchored in precision, clarity, and a deep appreciation for the learner’s strengths and context.

As you refine your assessment practices, remember that your work doesn’t occur in isolation. Lean on evidence-based frameworks, collaborate with caregivers, and integrate tools that strengthen your clinical reasoning. If you want to deepen your expertise further, explore our guides on functions of behavior, behavior intervention planning, and selecting pivotal skill targets—each designed to support your growth and reinforce best practice.

With every thoughtful assessment you conduct, you’re not just gathering data—you’re unlocking the path toward independence, dignity, and long-term success for the learners you serve.

Let this process be your anchor, your roadmap, and your opportunity to make an extraordinary impact.

References

5 Types of Bias in Data & Analytics. (2022, November 14). Cmotions. Retrieved January 4, 2023, from https://cmotions.nl/en/5-typen-bias-data-analytics/

Cipani, E., & Schock, K. M. (2010). Functional behavioral assessment, diagnosis, and treatment: A complete system for education and mental health settings. Springer Publishing Company.

Dipuglia, MD, BCBA, A., & Franchock, BS SPLED, L. (n.d.). VB-MAPP Scoring Supplement [Online PDF]. Penn State. https://storage.outreach.psu.edu/autism/70-Handout2_0.pdf

Dr. Ross Greene. (n.d.). https://drrossgreene.com/

Hanley, G. P. (2012). Functional assessment of problem behavior: Dispelling myths, overcoming implementation obstacles, and developing new lore. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5(1), 54-72.

Hanley, G. P., Jin, C. S., Vanselow, N. R., & Hanratty, L. A. (2014). Producing meaningful improvements in problem behavior of children with autism via synthesized analyses and treatments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 16-36.

Hanley, G. P., Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., Contrucci, S. A., & Maglieri, K. A. (1997). Evaluation of client preference for function‐based treatment packages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(3), 459-473.

LeBlanc, L. A., Raetz, P. B., Sellers, T. P., & Carr, J. E. (2016). A proposed model for selecting measurement procedures for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(1), 77-83.

Mehrzad, O. (2022, September 28). 3 Common Biases Affecting Your Data Analysis & Compromising Accurate Decision-Making - InnoVyne. InnoVyne Technologies. https://www.innovyne.com/data-analysis-biases-compromising-decision-making/

Oliver, A. C., Pratt, L. A., & Normand, M. P. (2015). A survey of functional behavior assessment methods used by behavior analysts in practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(4), 817-829.

Pelios, L., Morren, J., Tesch, D., & Axelrod, S. (1999). The impact of functional analysis methodology on treatment choice for self‐injurious and aggressive behavior. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 32(2), 185-195.

United States. (2011). Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. § 300.530 (f).

Witherup, L. R., Vollmer, T. R., Camp, C. M. V., Goh, H. L., Borrero, J. C., & Mayfield, K. (2008). Baseline measurement of running away among youth in foster care. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 41(3), 305-318.