Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP): The Complete Guide to Writing a Comprehensive Plan

A Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)—sometimes called a Behavior Plan or a Positive Behavior Support Plan—is the roadmap for reducing challenging behavior and building meaningful skills.

Typically included within a broader treatment plan or IEP, the BIP plays a key role in supporting a learner’s long-term success. It outlines:

Why the behavior is happening

How to respond when it occurs

What to teach instead

A well-designed BIP provides clear, actionable steps for addressing challenging behavior and teaching a functionally equivalent replacement behavior—a more appropriate way for the learner to get their needs met.

Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP): The Complete Guide to Writing a Comprehensive Plan

What Is a Behavior Intervention Plan?

How Does a Behavior Intervention Plan Improve Behavior?

When Does a Learner Need a Behavior Plan?

Determining which Function Controls Behavior

The Difference Between FA and FBA

Should You Choose an FA or FBA?

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

Types of Data Collected During Functional Behavior Assessment

Writing an Effective Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)

Steps to Writing a Behavior Plan

Components of An Effective Behavior Intervention Plan

Alternative or Replacement Behaviors

Additional Information for the Behavior Plan

Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Behavior Intervention Plan

Key Takeaways

A BIP should be based on a functional behavior assessment (FBA), which is a process of identifying the causes of a behavior.

The BIP should include a description of the target behavior, the replacement behavior, and the antecedents and consequences of the behavior.

The BIP should be written in a way that is easy to understand by the people who will be implementing it.

The BIP should be reviewed and updated regularly.

What Is a Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)?

A Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP) is a blueprint for changing behavior. In formal settings, it guides treatment and ensures everyone responds consistently. The plan includes interventions selected based on the hypothesized or demonstrated function of the behavior, with the goal of reducing challenging behavior by teaching more appropriate skills.

Outside of clinical settings, parents and caregivers can use a BIP to stay aligned on strategies and expectations. In both contexts, the plan helps everyone support the learner consistently and compassionately.

A BIP Is a Living Document

Although it’s written down, a BIP isn’t a static final product. It’s a dynamic component of treatment that evolves as the learner grows and responds to intervention.

Professionals continually:

Monitor the learner’s progress

Evaluate the effectiveness of interventions

Adjust strategies based on data

Revise the plan to shape behavior over time

While criteria may be embedded in the written plan, multiple revisions are typical and expected.

How Does a Behavior Intervention Plan Improve Behavior?

A well-written BIP doesn’t change a learner’s behavior on its own. In reality, it changes the behavior of the adults who support the learner. Meaningful change occurs when the environment changes.

A strong behavior plan provides:

Antecedent strategies to prevent or reduce triggers

Supportive responses to help the learner navigate difficult moments

Teaching strategies that promote functionally equivalent replacement behaviors

Clear guidelines for accessing reinforcement in appropriate ways

Effective implementation helps reduce reliance on challenging behavior by increasing the learner’s ability to get their needs met safely and appropriately.

Implementation Matters More Than Perfection

A behavior plan only works if the adults interacting with the learner follow it consistently. Many plans are written with unrealistic expectations—especially for parents, teachers, or RBTs in unpredictable environments.

High fidelity may be achievable in a clinical setting, but home and school environments are far more variable. A successful BIP must:

Speak to the intended audience

Offer realistic, actionable strategies

Anticipate real-world constraints

Support flexible, compassionate implementation

Ultimately, behavior improves because adults change how they respond, not because a document exists.

When Does a Learner Need a Behavior Plan?

Not every learner requires a BIP. For some, group contingencies or skill acquisition goals are sufficient. However, certain situations make a written plan necessary:

A learner may need a BIP when:

Challenging behavior impacts learning or daily activities

Safety is a concern

Multiple people support the learner and need consistency

Insurance requires a formal plan

Data indicates repeated patterns of challenging behavior

In Educational Settings

If a learner exhibits challenging behavior at school, staff should conduct a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) and develop a BIP. Under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), an FBA is required when:

A child with disabilities engages in behavior that threatens their placement

The behavior is a manifestation of the child’s disability

The behavior leads to suspension, removal, or loss of instructional time

This ensures the learner receives the support needed to access the curriculum safely and effectively.

Preparing to Write a BIP

Creating an effective Behavior Intervention Plan begins long before you start writing. To choose the right interventions, you need a thorough, well-rounded understanding of the learner and the context in which the behavior occurs. Relying on only one source of information increases the risk of missing important variables that influence behavior.

Gather information through direct observation, interviews, and document review from multiple sources. This should include:

Key Information to Collect

Comorbid diagnoses

Family composition and history

Target behavior(s) and operational definitions

Environmental variables

Antecedents

Consequences

Setting events

Additional details

Reinforcers

Interests

Strengths

Cultural variables

Know Your Audience

Your BIP must be written for the people who will implement it—whether that’s school staff, parents, RBTs, or insurance reviewers. Your audience determines:

The language level you use

The amount of technical detail

How examples are framed

The level of step-by-step guidance

A plan that’s too technical frustrates caregivers; a plan that’s too simple frustrates professionals. Aim for clarity, accuracy, and accessibility.

Use Tools That Support Function-Based Intervention

Research by Tarbox et al. (2013) found that professionals who used a structured, web-based tool produced significantly higher rates of function-based interventions in their BIPs.

The Master ABA Dojo is designed around this principle—providing resources, templates, and tools to support efficient, effective plan development.

Complete an FBA or FA First

Before writing your BIP, you must identify the function of each target behavior. This requires completing a:

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA), or

Functional Analysis (FA)

An accurate understanding of function is the foundation for every intervention in your plan.

Functions of Behavior

All behavior occurs because it serves a purpose. In ABA, the reason a behavior continues is called its function—what the learner gets or what the learner avoids. These outcomes act as reinforcers that maintain the behavior.

If a behavior no longer accesses its reinforcer, it will naturally fade and be replaced by a more effective behavior.

Why Identifying Function Matters in a BIP

A strong BIP always aims to:

Teach adaptive ways to access the maintaining reinforcer

Reduce reliance on challenging behavior

Sometimes teach the learner to tolerate when reinforcement is delayed or unavailable

To do this, you must accurately identify the exact function (or functions) maintaining the behavior. An incorrect hypothesis leads to interventions that don’t work—or worse, escalate behavior.

The functions of behavior are discussed in depth in our post Functions of Behavior in ABA: Complete Guide.

Determining Which Function Controls Behavior

FA vs. FBA: What’s the Difference?

Applied Behavior Analysis gives us powerful tools for understanding behavior, but it also brings a lot of terminology. Two concepts that are often confused are the Functional Analysis (FA) and the Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA).

Both aim to identify the function of a behavior, but they differ in:

Level of confidence in the results

Intrusiveness of the assessment

Ethical considerations

A functional analysis demonstrates actual control over a behavior by manipulating conditions. This produces highly reliable results.

An FBA, on the other hand, develops a hypothesis based on interviews, observations, and data collection.

Why the FA Became the “Gold Standard”

Many ABA programs teach that FA is the gold standard because:

The assessor manipulates variables directly

Control over the behavior is demonstrated

The results are more certain

But in recent years, many practitioners and autistic advocates have questioned the ethics of intentionally provoking challenging behavior—particularly when it may cause distress.

Ethical Note

Modern practice requires weighing the need for certainty against the learner’s dignity, safety, and emotional well-being.

Why Some Professionals Prefer the FBA

FBAs are less intrusive and rely on:

Interviews

Direct observation

ABC data

Historical information

However, FBAs still require observing behavior in contexts where challenging behavior is likely to occur—conditions that may be aversive for the learner. These ethical concerns mirror the debates around FA.

A Third Option: The Practical Functional Assessment (PFA)

Dr. Greg Hanley proposed the PFA (Hanley & Gover, 2018) as a more ethical and practical hybrid.

The PFA:

Uses interviews to understand what matters to the learner

Forms a hypothesis based on real-life priorities

Tests the hypothesis by demonstrating control in a safe, dignified manner

Avoids intentionally provoking severe behavior

This approach has become widely adopted because it balances data quality and ethical responsibility.

Should You Choose an FA or FBA?

Your choice depends on how confident you must be in the results.

Choose an FBA when:

A hypothesis is sufficient

You expect to refine treatment over time

The stakes are low and the behavior is not dangerous

Choose an FA when:

Inaccurate hypotheses could harm the learner

You need high certainty

You have the expertise to run it safely

Functional Analysis (FA)

A functional analysis systematically manipulates conditions to evoke and measure behavior. The professional:

Contrives specific conditions (e.g., demands, restricted attention, withheld items, and play/control)

Reinforces behavior when it occurs

Measures the rate of behavior under each condition

Demonstrates control when behavior occurs reliably in one condition

Because an FA seeks to evoke behavior, it must be carried out by a highly trained professional.

Recommended Resource

Brian Iwata, one of the most influential researchers in ABA, offers a detailed explanation of the FA in this interview. Anyone seeking deeper understanding should watch it.

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

A Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) gathers information about a learner’s behavior to understand the conditions under which it occurs. Unlike a Functional Analysis, an FBA does not manipulate variables. Instead, professionals use a combination of indirect and direct assessment tools—such as interviews, observations, and existing data—to identify potential patterns.

When consistent patterns emerge, the professional forms a hypothesis about the function of the behavior. It is essential to communicate that this is a hypothesis, not a confirmed conclusion.

Types of Data Collected During an FBA

The effectiveness of the FBA relies on collecting multiple forms of data from multiple sources. No single tool is enough on its own.

1. Indirect Assessment

Start with interviews and document review to gather background information, including:

Incident reports

Teacher or caregiver interviews

Parent questionnaires

Historical notes

These sources help identify:

Target behaviors

Potential triggers

Times/contexts where behavior is most likely to occur

Indirect tools provide essential context and guide the rest of the assessment.

2. Direct Observation: ABC Data

Antecedent–Behavior–Consequence (ABC) data are a core component of the FBA process. These data require observing the learner as the behavior naturally occurs, which may involve exposure to potentially aversive conditions.

ABC data help identify:

Antecedents: What happened immediately before

Behavior: What the learner did

Consequences: What happened immediately after

Tracking these patterns across multiple episodes helps highlight maintaining variables.

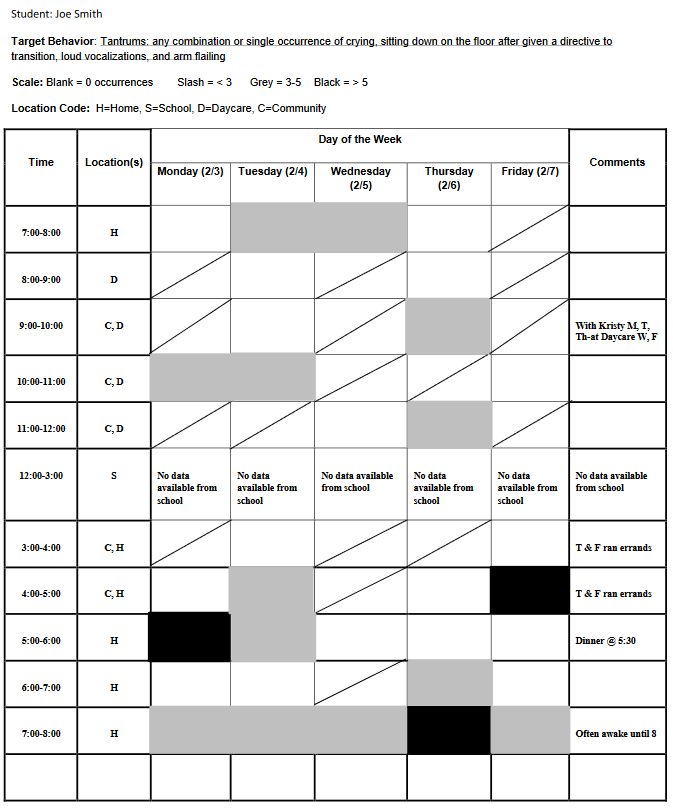

3. Scatterplots

Scatterplots document when behavior occurs across the day. They help identify:

Specific times of day associated with higher rates of behavior

Problematic transitions

Activities that predictably evoke behavior

Consistent patterns in frequency or duration

Scatterplot data complement ABC data by adding a broad, time-based perspective.

4. Supporting Documents and Tools

Additional materials can help clarify patterns, including:

Setting event checklists

Reinforcer inventories

Behavioral history

Medical or environmental notes

Treatment history

Each piece adds insight into the broader behavioral context.

The Importance of Setting Events

When using ABC data sheets—structured or free-form—be sure to consider setting events, which may significantly influence the likelihood or intensity of the behavior. These may include:

Lack of sleep

Illness

Hunger

Medication changes

Environmental noise

Changes in routine

Setting events often act as slow triggers, altering sensitivity to antecedents and consequences throughout the day.

Download Free Data Sheets Here

Below is an example of a scatterplot. The scatterplot offers a visual representation of the occurrence of behavior across different times of the day (or activities) and days of the week. This provides an opportunity to spot trends in the data you might otherwise miss.

The Competing Behavior Pathway begins to put all of the information you collect together while also considering replacement behaviors you might teach. It provides a visual display of common setting events, replacement behaviors and the ultimate desired behavior. Working through the process, allows you to consider both short- and long-term goals. How will the learner access the same reinforcer as the target behavior (short-term goal including a functionally-equivalent replacement behavior) and how will the learner engage in behavior that contacts reinforcement in the natural environment (long-term desired behavior)?

Competing Behavior Pathway Download

Collecting and analyzing the data for a functional behavior assessment takes time and patience. Professionals must consider all variables that might impact the behavior. Despite all of this, the professional cannot say for certain that they have identified the function of the behavior. The result of a FBA is always a hypothesis of the most likely function.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Many advantages and disadvantages exist for both functional analysis and functional behavior assessment. Understand the risks and benefits of each before you begin. If you are unsure about whether or not you should conduct one of these assessments, seek supervision from an experienced Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA®).

Both of these assessments are tools in the professional's toolbox that should be utilized when appropriate. Each assessment should be carefully considered before being implemented.

Choosing Between FA and FBA

Determining whether to conduct a Functional Analysis (FA) or a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) can be challenging—especially for newer professionals. In general, practitioners should choose the least intrusive, simplest procedure that is likely to yield effective, accurate information.

However, those two goals—minimizing intrusiveness and maximizing data accuracy—sometimes point toward different approaches. The guidelines below can help.

When to Choose a Functional Analysis (FA)

Select an FA when:

It is within your scope of competency, or you have a qualified supervisor providing oversight

You have access to a controlled environment where you can safely contrive conditions

The behavior presents limited danger to the learner or others

The risk of misidentifying the function is greater than the risks involved in conducting the FA

When to Choose a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

Select an FBA when:

A functional analysis is outside your competency, and no supervisor can safely support you

The behavior presents significant risk of harm

You cannot reliably contrive conditions with enough control to gather meaningful FA data

Law or policy requires an FBA

When an FBA Is Required

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), schools must conduct an FBA when a learner’s behavior:

Impacts their learning or the learning of peers

Puts their educational placement at risk

Results in removals, suspensions, or other changes in placement related to their disability

Sacramento State University provides a helpful fact sheet addressing frequently asked questions about FBA requirements in schools.

A Third Option: The Practical Functional Assessment (PFA)

As discussed earlier, Dr. Greg Hanley offers a third approach—the Practical Functional Assessment (PFA)—which combines strengths of both FA and FBA while reducing many of their disadvantages.

The PFA:

Begins with interviews to form a clear, learner-centered hypothesis

Uses this information to create conditions that safely evoke and terminate the target behavior

Demonstrates control over behavior with minimal risk

Requires training to implement effectively

This method has become popular because it is effective, ethical, and more contextualized to the learner’s everyday environment.

For additional details, see: Practical Functional Assessment (PFA).

Writing an Effective Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)

Writing a strong BIP takes practice. Always remember the purpose of the plan: it is written for someone else to implement. Your goal is to communicate exactly what you want the interventionist to do.

A high-quality BIP should:

Use clear, jargon-free language

Be specific, not vague

Provide step-by-step guidance where needed

Be structured in a way that makes sense to the people implementing it

Even small details of the plan’s formatting and organization can impact how effectively others carry it out.

Choosing a Behavior Plan Framework

When creating a BIP, you may organize the plan around:

A response class (multiple behaviors with the same function)

Common antecedents or functions

Individual behavior topographies

Each approach has benefits and challenges. Consistency is key—constantly switching frameworks across learners can confuse interventionists. Choose a structure that aligns with most of your learners’ needs and use it consistently.

Considerations When Selecting a Framework

Antecedent-Based Framework

Requires the interventionist to identify antecedents accurately and apply different strategies across conditions

May result in redundancy when the same interventions appear across multiple antecedents

Topography-Based Framework

Often leads to duplication, since the same interventions apply across different topographies that share a function

Response-Class Framework

Works well when behaviors serve the same function

Cannot include behaviors outside that response class

Requires multiple plans if behaviors fall into different response classesHere are some templates to help you compare the different options:

Behavior Intervention Plan Antecedent Template Download

Behavior Intervention Plan Topography Template Download

Complete Treatment Plan Template

Behavior Plan Formatting

Generally, agencies have a template they use when documenting behavior plans. Often the template dictates which framework you must use. This information will help you if you start your own business, provide contract or consultation services, or have the liberty to choose your own format when working for an agency. If you must use an agency template, consider how the format impacts implementation. Provide training to your interventionists to ensure treatment fidelity.

Below is an example of a behavior plan written in an antecedent framework.

BIP-Antecedent Framework

Formatting a behavior plan is a matter of structuring the information in a way that is easy for the interventionists to refer back to when needed. The image above shows an example of a behavior plan written in the antecedent framework. Each section provides interventionists with strategies for common antecedents (i.e. difficult task, low attention, etc.). The formatting of this plan allows the interventionist to quickly find the antecedent and then scan to find the interventions they should implement. There are limited instructions for implementing the intervention, but if the interventionist is familiar with the interventions, these might be sufficient.

When creating your plan, utilize headings and tables to allow interventionists to quickly scan to find the information they need. Bulleted lists break up text and distinguish one intervention from the next.

The Master ABA Dojo delves further into creating behavior intervention plans. Here, let's look at how to write a detailed plan.

Steps to Writing a Behavior Plan

Writing a behavior plan consists of many steps that do not involve sitting behind a computer screen. This is an active process that requires substantial data collection and planning. The steps below are a guide, but remember that you may need to add steps depending on your setting and the rules in your area.

Acquire informed consent from the parent or guardian

Collect baseline data

Collect FBA or FA data

Analyze the data to identify a hypothesized or tested function of the target behavior(s)

Research appropriate interventions

Assemble the components of the plan

Review the plan with the human rights committee if the plan includes any form of seclusion or restraint or if otherwise required (know the laws and rules for your specific area)

Review the plan with the parent or guardian and obtain a signature

Train staff to implement the plan

Components of An Effective Behavior Intervention Plan

Several components come together to create a complete treatment package to address maladaptive behavior and each component builds the foundation for positive behavior change. While some elements may be optional based on the setting or other supporting documentation, all plans should include the following components.

Identifying Information

Ensure that all staff know without a doubt whose plan they are reading. Include sufficient identifying information to make this crystal clear. Appropriate identifying information includes:

Child's name and any nicknames

Child's date of birth

Date of the plan (to ensure staff recognize the most recent plan)

Date of plan revisions

Author

Supervisor

Setting (if appropriate)

Goal

Clearly identify the goal for the plan. Anyone reading the plan should understand the purpose behind the plan. Why is this behavior intervention plan necessary? What benefits do you hope to see for the child?

Take a look at the following examples:

Good:

Goal: To help Beth stay in the classroom without disruptive behavior.

Better:

Goal: To increase Beth's ability to remain in the classroom and participate in classroom activities with her peers with a decrease in target behavior and an increase in adaptive alternative behavior.

Best:

Goal: To increase Beth's ability to remain in the classroom to 95% of the school day and actively participate in activities with her peers with a decrease in noncompliance to <10 minutes/day and an increase in requesting staff attention to 75% of opportunities.

Writing a goal that is observable and measurable ensures that everyone involved is on the same page. Clarity is crucial throughout this process.

Target Behavior Definition

Target behaviors should be defined operationally, meaning that anyone reading the definition can identify whether or not the behavior is occurring. For more information on writing operational definitions, see the post: Operational Definitions: Clearly Define the Behavior. In this post, I discuss the difference between topographical and functional definitions and provide examples of each.

Here's an example that builds on the goal for Beth above:

Noncompliance: Any instance in which Beth physically and/or verbally refuses to comply with a directive for a skill previously demonstrated for longer than 30 seconds.

Examples include:

Shouting "no!" and crossing her arms when asked to touch her head.

Sitting down on the floor when told to line up for music.

Running out of the room when told to sit at the table.

Non-examples include:

Crying while touching her head when asked to touch her head.

Saying "I don't want to" while walking to the line when told to line up for music.

Standing still for 15 seconds before walking to the table when told to sit at the table.

Onset: 30 seconds. Offset: 30 seconds.

Hypothesized Function

Based on the assessment data (FBA or FA) you collected, write a statement describing the hypothesized (or tested if you conducted an FA) function of the target behavior(s). This statement helps keep everyone involved clear on the factors that likely maintain the challenging behavior. Learn more about functions of behavior in our post Functions of Behavior in ABA: Complete Guide.

Check out the statement for Beth's scenario:

Hypothesized Function: Based on Functional Behavior Assessment data, including interviews with staff, ABC data, scatterplot data and direct observation, Beth's noncompliance is likely maintained by access to staff attention in the form of reprimands, coaxing or chasing.

Antecedent Interventions

Antecedent interventions minimize challenging behavior by addressing common triggers, setting events, or other precipitating factors. Clearly understanding the conditions within which the behavior typically occurs improves the accuracy and effectiveness of your interventions.

For more information about antecedent interventions, see the post: Antecedent Interventions: Complete Guide. In this post I discuss several effective antecedent interventions as well as when to implement them.

Here, let's look at antecedent interventions for Beth:

Antecedent Interventions:

Visual schedules: Using a visual schedule may reduce the motivating operation (MO) for Beth's noncompliance as staff review the schedule with her prior to each transition, providing opportunities for staff attention routinely. In addition, include on her schedule multiple activities that include opportunities for her to receive staff attention (i.e. reading books, playing a math game, taking a walk in the hall).

Assigning "helper" tasks: Many of Beth's challenging behaviors occur during transitions when staff may be attempting to gather materials, thus diverting staff attention. Assigning Beth "helper" tasks during this transition provides Beth with positive staff attention while minimizing the time staff's attention must be diverted. For example, ask Beth to help you carry books to the circle area.

Alternative or Replacement Behaviors

Whenever you attempt to reduce one behavior, you must include a plan for teaching an appropriate alternative or replacement behavior. If you fail to include this, the child will develop her own replacement behaviors and they may be problematic. The replacement behavior should serve the same function as the maladaptive behavior you are looking to reduce.

Check out this example for Beth:

Replacement Behavior:

Functional Communication Training (FCT): Teach Beth to many appropriately for attention. When Beth is likely to engage in target behavior (i.e. before a transition when your attention may be diverted), but prior to onset of the target behavior, prompt Beth to request staff attention by saying "talk to me," "watch me," "look at me," or some similar form of requesting attention. If Beth engages in target behavior, withhold attention and try again at another opportunity.

One way to teach replacement behaviors is through social stories. Read the post Autism and Social Skills: Complete Guide for more.

Consequent Interventions

Every behavior plan should include some form of reinforcement strategy for appropriate behavior. Specify what the schedule of reinforcement should be and include what behaviors staff should reinforce. The post Understanding Consequence Interventions: Punishment vs Reinforcement goes into more about these types of strategies.

For Beth we will use the following intervention:

Consequent Intervention:

Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA): Beth should earn reinforcement (i.e. focused staff attention in a playful manner) each time she uses a functional statement to request staff attention.

IntervalR+ ScheduleR+ Time1FR130 seconds2FR21 minute3VR32 minutes4VR53 minutes

Criteria for interval progression: <10 minutes/day for 3 consecutive days

Criteria for interval regression: >20 minutes/day for 3 consecutive days

Response to Target Behavior

In this section, you will include specifics regarding how staff should respond when the target behavior(s) occur. This should include criteria for crisis response as well as when and how staff should call for help.

Beth's behavior is reasonably mild, so staff's response should reflect that:

Response to Target Behavior:

Withhold attention to the extent possible (i.e. do not say Beth's name, do not make eye contact, etc.)

Monitor for safety

Use body positioning to minimize opportunities to elope from the room

Present the demands with visuals when possible

Wait for compliance with initial demand

Resume reinforcement schedule only once compliance has been re-established

Additional Information for the Behavior Plan

At times, additional information may be relevant. This might include common setting events such as specific staff, the presence of loud noises, or being hungry (see our post ABC Data: The Key to Understanding Behavior for more). Include any other information that might help staff understand and respond to the behavior appropriately.

Keep this information related to the target behavior(s), even though you might want to include extraneous information. For example, do not include information about the child's toileting schedule unless the behaviors occurs around toileting.

Let's see what might be relevant for Beth:

Additional Information:

Beth often engages in a higher rate of behavior on Mondays and Fridays.

Beth typically reacts negatively to loud noises such as fire alarms or assemblies.

Beth's Behavior Plan

The best way to learn is through examples. Download Beth's behavior intervention plan for future reference.

Beths Behavior Intervention PlanDownload

Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Behavior Intervention Plan

To determine whether your BIP is working, you must collect ongoing data. Although data sounds like a scary, scientific word, it's just a way to measure the behavior. Refer back to your goal to choose the best measurement technique for your plan. Here are some common options:

Frequency (count how many times the behavior occurs)

Duration (measure how long the behavior occurs)

Intensity (use a scale to measure how intense the behavior is)

In the example used throughout this post, Sarah's aggression should be measured using a frequency count. Simply count the number of times Sarah makes physical contact with another person. If she engages in fewer instances of the behavior, your plan is working.

Don't abandon your BIP if the behavior doesn't immediately change or even if it gets worse for a little while. These are common occurrences once you begin intervening on challenging behavior.

References and Related Resources

Brodhead, M. T. (2015). Maintaining professional relationships in an interdisciplinary setting: Strategies for navigating nonbehavioral treatment recommendations for individuals with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(1), 70-78.

Cipani, E., & Schock, K. M. (2010). Functional behavioral assessment, diagnosis, and treatment: A complete system for education and mental health settings. Springer Publishing Company.

Hanley, G. P., & Gover, H. (2002). Practical functional assessment: Understanding problem behavior prior to its treatment.

Hanley, G. P., Jin, C. S., Vanselow, N. R., & Hanratty, L. A. (2014). Producing meaningful improvements in problem behavior of children with autism via synthesized analyses and treatments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 16-36.

Hanley, G. P., Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., Contrucci, S. A., & Maglieri, K. A. (1997). Evaluation of client preference for function‐based treatment packages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(3), 459-473.

Horner RH, Sugai G, Todd AW, Lewis-Palmer T. Elements of behavior support plans: a technical brief. Exceptionality: A Special Education Journal. 2000;8:205–215. doi: 10.1207/S15327035EX0803_6.

Kroeger, S. D., & Phillips, L. J. (2007). Positive behavior support assessment guide: creating student-centered behavior plans. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 32(2), 100-112.

LeBlanc, L. A., Raetz, P. B., Sellers, T. P., & Carr, J. E. (2016). A proposed model for selecting measurement procedures for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(1), 77-83.

Pelios, L., Morren, J., Tesch, D., & Axelrod, S. (1999). The impact of functional analysis methodology on treatment choice for self‐injurious and aggressive behavior. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 32(2), 185-195.

Quigley, S. P., Ross, R. K., Field, S., & Conway, A. A. (2018). Toward an Understanding of the Essential Components of Behavior Analytic Service Plans. Behavior analysis in practice, 11(4), 436-444.

Schwartz, I. S., & Baer, D. M. (1991). Social validity assessments: Is current practice state of the art?. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 24(2), 189-204.

Tarbox, J., Najdowski, A. C., Bergstrom, R., Wilke, A., Bishop, M., Kenzer, A., & Dixon, D. (2013). Randomized evaluation of a web-based tool for designing function-based behavioral intervention plans. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(12), 1509-1517.

United States. (2011). Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. § 300.530 (f).

Vollmer, T. R., Iwata, B. A., Zarcone, J. R., & Rodgers, T. A. (1992). A content analysis of written behavior management programs. Research in developmental disabilities, 13(5), 429-441.